This article is about the reflective crystals seen deeper in caves, in the dark zone well away from sunlight influences.

| Contents |

|---|

| Introduction |

| Where are they found in caves? |

| Some special cases |

| Tourist Do's and Don'ts |

| Discussion |

| References |

Introduction

Deep within limestone caves, one can sometimes see small

reflective calcite crystals.

If you look at them closely you can see that they are sometimes made up from

a myriad rough surfaces but all oriented one way so that the light catches on one

side at one angle, and another side at a different angle.

This is very common with calcite, and also tells you that the surface is

most likely dry. Wet calcite tends to look waxy.

Generally if there is water on the crystal surface, it looks a little

dull, but if the crystal is dry, it can be very sparkly. Pool crystal is

an exception: some slow-growing pool crystal can disperse light while

underwater, possible because the active growing crystal surfaces form a

bevel whose angle is just right to make rainbow colours.

The size of individual calcite crystals is determined by the length of time that

it took to form the crystal, with small crystals growing faster than large crystals.

Where are they found in caves?

Showcaves are a great place to see calcite crystals in their natural positions.

Generally crystals are seen on the surface of dry speleothems such as

stalactites, stalagmites and flowstone.

The whole sparkling effect is best seen with a light source at an

angle to the crystals, a special skill developed by professionals who light

show caves, as the best angle varies from site to site.

Calcite has different optical properties to other materials which is why

simple showcave illumination can make a cave look very special. However

too much light for too long can allow weeds to grow and spoil the

effect! Also, some light spectra can enhance or kill micro-organisms.

Occasionally crystals are deposited on the bedrock - see

Some special cases below.

They can also occur on clastics (mud through to pebbles) from

dripping or splashing water.

|

In this old 1990's photo of a nice spot at Jenolan Caves,

we can see a lot of pool crystal and flowstone sparkling (white dots)

in the light of the camera's flash.

The rounded ball shapes in the foreground are calcite, generally formed under water, when the area had a shallow pool. The crenulated shapes in the lower right are microgour calcite flowstone, and would have held pockets of water. In the middle is a lower part of the pool, and on the left side small sparkles indicate that its base was once flowstone, deposited when there was no water in the pool. There is also a raised edge to the lower pool, also sparkly with calcite, when there was water in the pool and this raised edge was deposited very close to the pool surface forming a small rimstone dam. The scale here is about 2m from left to right. |

|

Sparkly calcite on mud

|

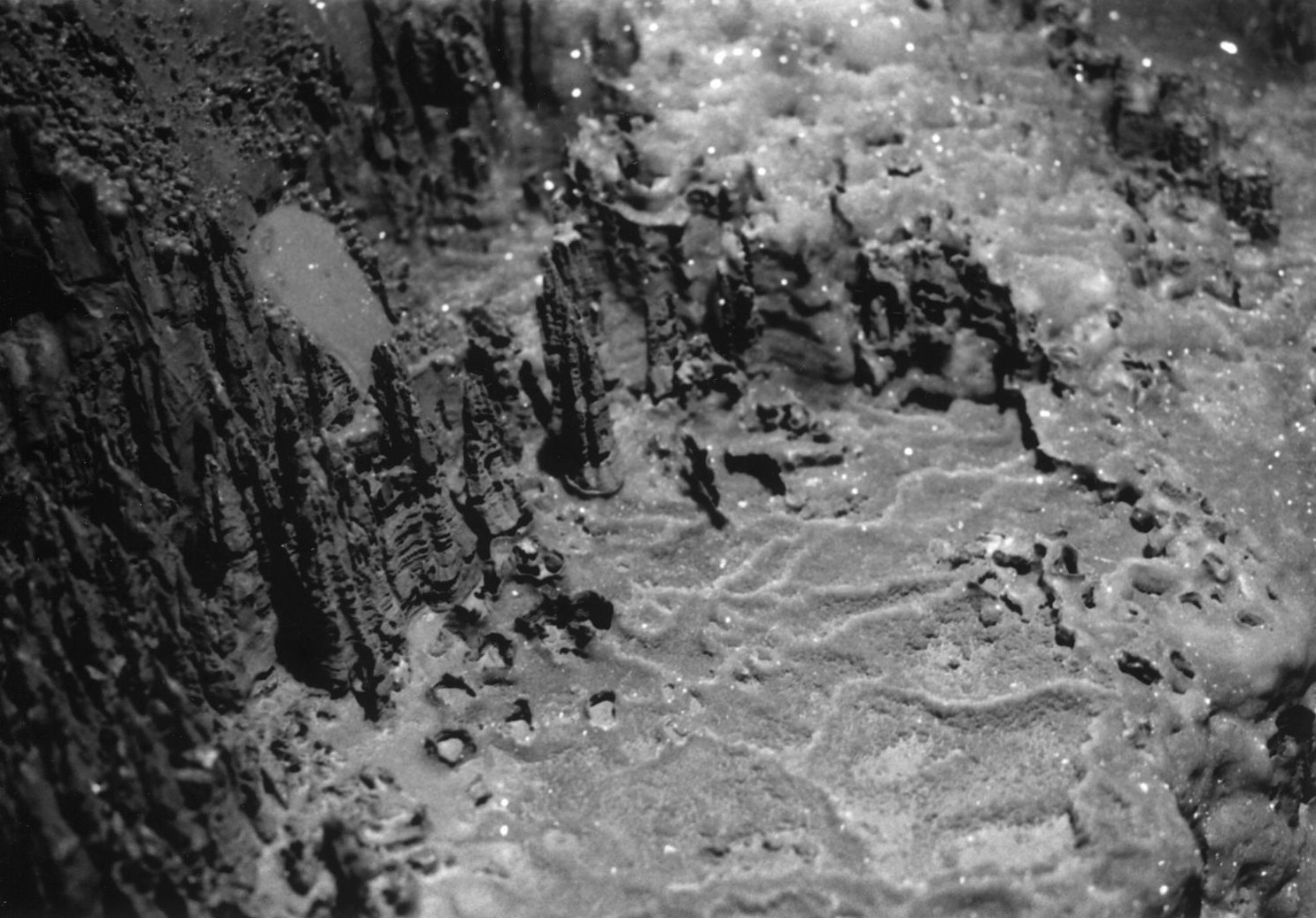

In this old 1990's black and white photo of another spot at Jenolan Caves, a small

area of about 20 to 30 cm across has sparkling dry calcite flowstone deposited on clastics.

The area can be wet at times, so this is likely to be a temporary view. A deposit of cave mud (clastics comprise everything from clay to rocks) has been slowly dripped on so that small pebbles temporarily protect underlying soft clay and other pebbles. This results in the little towers. Later, limy water slowly overflowed the area, outgassing CO2 and deposited calcite as little rimstone dams and microgours. When dry, the facets of the calcite sparkle. Some of the clastic tower shapes have collapsed and have been washed away leaving little rings of calcite near where they stood. Towards the top left is a flatter sloping oval area with sparkling calcite: this will in time become a stalagmite. |

|

Some Special Cases

A tiger-striped stalactite? While photographing a cave scene at Jenolan, we noticed that the calcite crystals on a drapery were all lined up forming almost horizontal bars (depending on your viewpoint) that reflected the light of the cap lamp. This was a quirk of the growth of this drapery, suggesting that it grew very slowly indeed to allow such large crystals to grow.

|

This is part of a scan of an old 1990's slide of a scene deep in one of the caves at Jenolan.

The left-hand shawl has a white reflective line running across it, and others can be seen

faintly above it.

The light line is a reflection of the flashgun's light on an array of calcite crystals

which are all lined up in the same direction.

Generally, if calcite grows slowly, the crystals grow larger. In a shawl, this could be caused by a slow drip rate, no evaporation (only CO2 gas exchange), water slightly saturated with carbonate, and few other impurities. The shawl has a stalactite growing at its lower edges, and the more recent calcite deposited on the lower right-hand edge appears to be more radially deposited (calcite c-axis at 90° to the edge), suggesting a more conventional fast moving droplet type of formation compared with the older deposit with the stripes. At the time of photography, the cave was quite dry. The right-hand picture gives more context, showing a second drapery to its right. The light coloured dots on the right-hand drapery are reflections by smaller groups of calcite crystals in the flash photo. In the background, bedrock points are caused by solution of limestone in steeply-dipping beds, possibly when the chamber contained more gravel and water, long before the speleothems were deposited. From my memory of the trip, we were rather distracted by the rest of the scenery and only noticed the striped stalactites and shawls in the ceiling as we were packing up! |

|

|

Reflective Dots on the Bedrock? Other crystal coatings:

While inspecting a privately owned cave at Walli, NSW, reflective dots were seen on

parts of the bedrock. Some dots were more reflective than others, with the more

reflective ones being a thin coating containing single crystals of barite.

Gypsum coatings were not quite as bright in the cap lamp, and some

crinoid ossicles in the bedrock were surprisingly reflective.

The barite was most likely deposited from warm mineralised water, as these caves

have hydrothermal features caused by warm water circulating deeply in faulted

limestone.

|

In this photo of the wall in one of the caves at Walli,

small diamond-shaped reflective dots are thumbnail-sized

clear crystals on the surface of the dark grey limestone.

Using one's cap lamp, the more distant walls reflected quite strongly but when one was closer, the effect was less noticeable. This was due to the angle between the eye and the light beam, so the more distant "corner reflectors" of barite were more obvious. |

|

For a more technical discussion of this phenomenon, please see the Walli section of chapter 3 in my thesis, Articles 2004b around pages 205 - 208: Articles

Tourist Do's and Don'ts

- Don't go round poking them. Treat them the same way as you would some piece of artwork: admire and look but don't touch. They only feel like rocks.

- Sometimes, the showcave guide passes a broken piece of crystal around during the tour so that people can feel a speleothem and note how heavy it is.

- Take care when caving so as not to disturb crystals as you move through a cave. Try not to brush against them as it spoils them.

Discussion

The reason why one does not see these crystal facets so much

outside of caves is because there is usually not a point source

of light to illuminate particular crystals, and because it does

not take long for plants to grow over calcite surfaces outside

of a cave.

In a show cave, one can get very different lighting effects

using different types of lights. Most high power white LED lights

use a pulsed power supply which looks good in a static display,

but flicker is noticeable if the light (or the viewer) moves.

Using a hand-held light, this can be used to some advantage by skilled

showcave guides to illuminate particularly sparkly dry flowstone.

A filament lamp gives a very different effect, and the light

source's position must to be moved more before the crystal facets

can be noticed, due to the length of the filament.

The sparkly effect is generally unable to be seen by fluorescent

light, again mainly because of the width of the lamp.

Back in olden days, candles would show up the sparkles well, until

soot covered everything!

References

There are many general references online to cave lighting so

a general search may bring up something in your area.

For a general discussion about cave calcite, crystals and forms,

see the references on the main page, for example,

Cave Minerals of the World.

Content updated 15 January 2026.